A work of short fiction inspired by the stories of desi gas station attendants in New Jersey.

I didn’t find Parul. She found me.

If she had ridden up on horseback and swung me onto her saddle, it wouldn’t have been far from the truth. But that’s not what she did. She appeared on the bounding wall of the basketball court, the red instep of a high heel flashing, one leg swung over the other, in a white salwar-kameez, a camera across her shoulder and one of those shiny bags with ‘Ps’ written all over that you see on the sidewalks of New York City. That’s the picture of her that’s always in my mind.

Even now, two years gone, earning good money, with a car and a flat, and no woman waiting in the wings for me, that’s how I see her. On my desk is a Manila envelope from my mother, with some woman’s photographs and a bio, to try and make me agree to an arranged match. She’s probably scanning the matrimonial classifieds in the paper right now, looking for a good Punjabi girl with the right height and weight and a job-worthy BA. And that’s when I think of Parul. The way she showed up, like an apparition on the wall. I caught sight of her in one blazing instant on a day that was otherwise perfectly ordinary. Just Afzal and I shooting hoops at night like usual with the guys after work.

She was staying with her aunt, visiting India and taking courses in Quality Assurance testing at the polytechnic. A lot of the students were from abroad; it was simply cheaper to pay Indian rates and still get a first class certificate than study in the U.S. and shell out dollars. Afzal and she got talking at a local coffee shop, he invited her to meet his friends from work after a basketball game one night and that’s how I came into the picture.

“She’s from Cincinnati,” Afzal told me, waving at her. She waved back and smiled. He liked to tease her and say she was an escapee. Running away from her dad’s grocery store in a suburb of Cincinnati. Parul worked there in the daytime.

“That’s partly true,” she would nod, “I needed a break from that place. I crossed a whole ocean just for that purpose.”

But I learnt all this later. That first time I saw her at the basketball court in Vikasgarh, I had this sense that she noticed me. When I chased the ball to the edge, my head down between my legs, I saw her face, upside down. She was smiling, at me. She had a round face, high forehead, shiny skin, long black hair up to her shoulders and she’d got on lipstick. I stood up slowly, and I looked at her, right side up.

Her clothes had that gleaming dust-free whiteness that Indian clothes never retain. Must be the water or the air, but something ends up yellowing our whites. And her skin gleamed – she was so chikna, smooth – skin that escapes a burning sun for half the year.

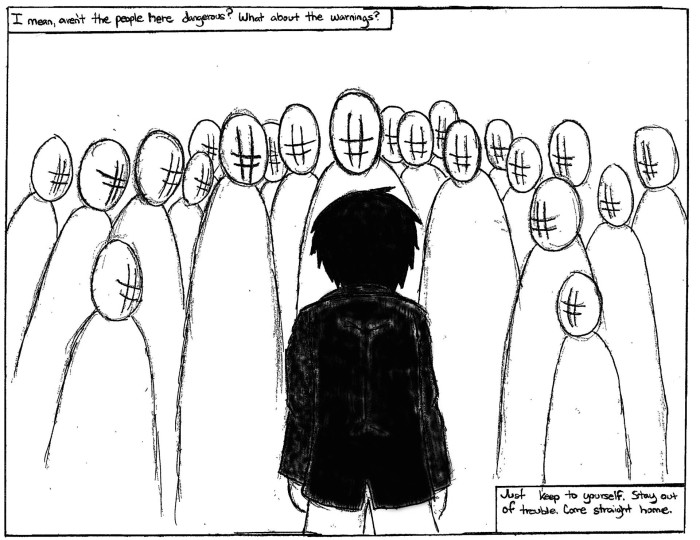

I had been back in Vikasgarh, back in India for a year now. The guys at the gas station in Jersey had told me I was crazy to leave. I knew I was crazy to leave. My father had died suddenly of an asthma attack – too many years spent on the seats of tractors on the big wheat farms, breathing in dust and husk. Returning for my father’s funeral would mean I would not be able to set foot in the States for a long time. That was the penalty for overstaying. And I had overstayed my tourist visa by a year then, working at my uncle’s gas station.

“Your tears are a luxury,” they said. “You can afford to cry. What price did you pay to get to Jersey? An air ticket. We paid with time and fear.”

“Not my tears, my mother’s,” I’d said.

I was thinking of these things as I looked at Parul on the bounding wall. I began to walk towards her, though it was really her gaze that pulled me in. It was true that I was far better off than the men I’d worked with at the gas station. I’d come in on a tourist visa sponsored by an uncle, and he’d asked me to stay over, join him in working at the gas pump he owned, make some money until I’d saved enough to pool in with him and buy my own station. I did exactly that—a 22-year-old man without a job had little to lose, but things didn’t work out. I made some wrong moves and ended up owing my uncle some money. I got on his wrong side. And then came the phone call from my mother.

My father was a strapping 55-year-old man with a breathing problem but no one expected him to die of it. I knew I had to leave when my mother called. I wanted to. There was no one else with her. No siblings, I have none, and she has none. Sitting in the Air India plane back to Vikasgarh, watching the boats on the blue Atlantic grow smaller and smaller, I felt I was watching the great, growing canopy of my dream, my dream of America, shrink into a table napkin, a pretty, blue and white checkered napkin with the sun on it, pretty and common and suddenly useless.

When I met Parul a year later in Vikasgarh, I was working as a teller in a bank, dishing out cash. The degree I earned in computer science six or seven years ago, sat packed away with certificates and gold heirlooms and a passport in a safe in my mother’s flat. In the nights I learned how to speak English with a Chicago accent and a Scots accent—or what they called ‘accent neutralization’—at Rawlins’ Academy. If I could land a job at a call center at the end of it, I’d earn something you could call real money, but the English skills weren’t working out. My Punjabi accent was too strong. I didn’t grow up on the streets of Vikasgarh, playing cricket across the road, ball rolling between car tires, and hustling cigarettes and lottery tickets on street corners for nothing. The big technology firms didn’t want my computer degree or me. The market was down; there were too many graduates. It would have to be a call center job for now.

“Are you Afzal’s friend?” Parul called out, swinging her leg as I strolled toward her.

I nodded. Afzal came over. I took my time walking up, dribbling the ball.

There was this thing she did with her shoulders when she talked—a half-tired, dance-like, rippling move that was so sudden I worried she would fall off the bounding wall. Her shawl fell instead, and there was the outline of her breasts, little handfuls, sitting beneath the transparent white cotton Kameez. I blushed a little, bent to pick up the shawl and hand it to her.

“Afzal tells me you’re American,” I said.

“I grew up in the States but I’m all Punjabi. As Punjabi as you.”

“Why am I so Punjabi?” I grinned, bouncing my ball.

“You swear harder than you play,” she laughed. Her shawl kept slipping off her shoulders and she kept draping it back on. It was November and the cold was beginning to make the mornings foggy. The Vikasgarh smog blurred the sun, and the cold weather dimmed it further. Behind her the light made orange rivers in the sky.

“Actually, I swear better than I play,” I said.

“I’d have to talk to you a little more before I give you that,” she said, resting her chin in her hand and tilting her head up at me like a cocky kid.

“Kunal,” she repeated, when I told her my name. “See you later Kunal,” she said and hopped off the wall.

“How soon is later?” I said, and she grinned.

I thought about her all the way to my place, a room in a paying guest suite that I shared with Afzal and a couple of other guys.

I wondered what she would think if she knew I had pumped gas in New Jersey. I didn’t talk about it to anyone in India, and only my mother and Afzal knew about it. If I could afford a plane ticket and had a degree in computer science, what was I doing working at a gas station. Is what people would say. You didn’t mention these things among folks like us.

For the first weeks that Parul and I went out, it was with friends. We were always sitting beside each other at the movies, but I could not work up the nerve to ask her out on my own. I wished there was a club or a night place to go with her but Vikasgarh is a desert for lovers.

“You’ve got to do it,” said Afzal, “she’s leaving in three months I think, back to the States.”

“There’s no point.”

“Give it a shot.”

We were drinking beers at a restaurant one evening, Afzal, me, some others and Parul.

“Is there anything to do here in Vikasgarh? Other than restaurants and movies?” Parul asked.

“There’s the zoo,” I said, looking at the gates.

Afzal piped up. “Kunal will take you. He likes the zoo.”

“The zoo?” she looked at me with sly eyes. “You like the zoo?”

I snatched a glance at Afzal and said, “If you like to walk, yes, it’s a place to go.”

“I like walking. I like animals too,” she said, grinning. She had nice teeth, not very white, not very small, but just a pretty smile. And that was our first date. The next day I asked her to a movie, just the two of us. She asked me to tell her about my tattoos. I had rolled up my sleeves. There was a dragon on my right arm and a mountain on my left.

“The dragon was my first tattoo. I wanted something fierce. Blowing fire. Macho. That sort of thing.”

“But you’re not at all macho.”

“I’m not, that’s true,” I said and laughed.

“And the mountain?”

“The mountain is for Vaishno Devi. I took my mother there on pilgrimage, up in Kashmir. You know? Near the Himalayas?”

She nodded her head.

“I wanted to remember the trip, so I got the mountain.”

“You’re such a good son,” she said. Her eyes were bright and happy. “You climb mountains for your mother.” We began to laugh. “What’ll you climb for me?”

“I’ll climb your aunt’s gate.”

“But I have to invite you first.”

I looked at her. She sidled up close. Maybe that was when we held hands.

“She’ll kill us both anyway. You wouldn’t.“

“I would. I’m a better gate climber than a mountain climber.”

We sat in the back and kissed. When I dropped her to the auto-rickshaw stand, it was all I could do to not kiss her again. In Vikasgarh, you don’t even hold hands in public.

All of the next day at work, I wanted to be near her and we texted. My heart felt full. The problem now was finding a place she and I could be together inside. I convinced Afzal and the guys to leave us alone in the late afternoons after work. I couldn’t go on overnight trips with Parul because she had to be at her aunt’s place every night. This meant that I took days off and she skipped class. I was with her every day except the weekends, which she spent at home with her aunt.

Parul knew her way around my body; I wasn’t her first. This was new to me, because she wasn’t timid, or coy. Not Parul. She wanted me. I figured it was an American thing, for such a young woman, just out of college herself, to not be a virgin, and though it bothered me somewhere, I didn’t let it stick around in my head.

What stuck in my head was a day she was lying next to me and squeezing my shoulder, running her fingers all over my back.

“Tell me about the time you pumped gas in Jersey City,” she asked, “what was it like?”

“Nothing special. I did the work. One of the regulars who used the station once told me that I should go to college. Not waste my time doing this. And when I told him I had a degree, he just stared. ”

“Do you think of going back?”

“I can’t. I overstayed my visa, right?”

“Have you thought of what will happen when I leave?”

I had tried not to think of it. “Of course I have. I don’t know what we can do about it. Unless –” I added, “Unless you stay on.”

“I can’t stay on indefinitely. I have to go back, dad’s business is there, and that’s where I live.”

“Don’t go back,” I said, “Not yet,” and we kissed.

“You really want me to stay,” she whispered happily. She made that move with her shoulders, that dancing move she made the first time I saw her on the basketball court, and tiny thunderbolts moved through me.

We didn’t bring it up again—the question of how to go forward. I didn’t want to press her to stay and she wasn’t saying much about it. But the idea of her getting on a plane and leaving without me rankled.

One thing that amused her endlessly was when I called her baby. It was a new word for me—an American word, one I’d only heard in movies—but I wanted to try it out, see how it rolled off my tongue. She was combing her hair in the bathroom of a hotel room—there were six hotels in Vikasgarh and we went through each one. Vikasgarh is a small place so we didn’t risk staying too long or repeating hotels. After we went through all six, we were back in my paying guest suite. If I got the day off, we’d check in in the morning and check out in the evening, since nights weren’t possible with her aunt around. Not the five star luxury places, but the oddball ones with window air-conditioners and stuffy corridors. She didn’t care as long as the sheets were clean, and they never were. So we went sheet shopping.

Vikasgarh is famous for its textile mills. I took Parul to the fabric markets on my motorbike—rows of shops sitting side by side, doorless but protected by metal shutters during nights and holidays, all opening into a single long corridor with painted, concrete poured floors. The shopkeepers called out to us from raised platforms with fabric, bed sheets and bands of cloth rolled behind them in shelves. Parul and I walked into a store and the sardar who ran it leapt to our service. Parul’s American accent must have caught his ear. We were ushered into great old chairs dressed in faux-velvet, while the sardar flung open cotton sheet after cotton sheet. I made a great show of feeling the material carefully between my fingers.

“Softer. We need softer,” I said very seriously while Parul sputtered over the chai the bus boy in the store brought to her.

“150 thread count! Top quality!” the shopkeeper snapped his fingers.

“Sheets for bedroom or guest room? Special occasion?” he asked.

“Special occasion please,” I answered again, with the gravity of a householder. After an hour or so of this, we picked a set and raced back to the hotel with it, laughing endlessly when we remade the bed. On that day, she had a towel on and I had forced myself into the bathroom. I sat on the floor and watched her in the mirror. She had frizzy hair. She was running her fingers through it to get the knots out. I offered to help but she said no. I offered a massage but she said no. So I pulled off the towel and wouldn’t give it back. “You look good without it,” I said, with a pause, and then added, baby. She began to giggle.

“You say baby so awkwardly, as if you’re saying excuse me. Excuse me madam, you just dropped a dollar bill…baby, you just dropped a dollar bill.”

I must have looked embarrassed because she gave me a hug. “No, no, it’s sweet, just not your style. Can’t I tease you?” For some time after that whenever we bickered, I’d say baby something, in my strongest Punjabi accent and she would begin to laugh.

It was the middle of the afternoon and we were squeezed into the single couch in the room, watching TV. Her hair was still wet on my shoulder.

“Remember you asked me about my time pumping gas in Jersey City?” I said, “The plan was to join my uncle in the business, but I’d racked up some debt. I was visiting casinos and I owed money. My uncle took care of the loan but whatever I earned went to paying him off.”

“Your mother must have freaked out.”

“She doesn’t know… But I’ve never gambled again. No betting, no cards, nothing.”

“And your uncle? What did he say?”

“He threw me out of the family business. He wouldn’t give me a second chance.”

She looked up at me, thoughtfully.

“It’s behind you now.”

“I’d like to think so. It was a huge mistake.”

“But it’s over. Does anyone else know?”

“No one, only you.”

We let the TV run. Finally she sat up and ruffled my hair.

“You have red flags written all over you now! What’re you going to tell me next?”

“That’s it,” I shrugged. “That’s the worst thing I ever did. You know now.”

She punched me lightly in the arm. We were quiet again.

“And you? What are you going to do with that Quality Assurance certificate when you go back?” I asked.

“My folks want me to settle down,” she said softly, her eyes on the television.

My belly tightened. I twisted a lock of her hair around my finger and played with it, saying nothing, because what I wanted was to say something about her and I settling down. But that would mean leaving Vikasgarh for Cincinnati. This was no place for her. And leaving Vikasgarh would mean leaving India, leaving my mother. We were still going through my father’s things. She was still grieving.

In the end, her aunt found us out. Her hosts—uncle, aunt and cousins—were attending a wedding in a village fifty miles north of Vikasgarh for a week. Parul and I grabbed the chance and moved into the empty house. We drove to the sugarcane fields outside the city, ate in roadside shacks, and came home to her aunt’s place, pretending without saying so, that we were a couple with a future, living a couple’s life. We cooked together and watched movies late into the night. I brought her coffee in bed and she rolled rotis for me for breakfast. The thrill – the greatest thrill – was not having to part at five in the evening. Just knowing that we could watch the street lights come on, and change into nightclothes and wake up in her bed…there was nothing like it.

The aunt and family showed up two days early in the middle of the afternoon and found us on the couch, watching TV. They told me to get out. I protested as I left, gathering my wallet. I shouted, “Parul, say something!” But Parul, for all her boldness, was quiet, for once. She retreated into an inner room while her family threatened to call the police. For two weeks I heard nothing from her despite texts and phone calls, until one afternoon when she texted me saying,

“My mother’s here. We’re leaving for the States in a week. Can’t leave the house.”

I called my mother. I needed her—my reinforcements. I was going to see Parul before she left. I was going to see if I could stop her, somehow. I texted Parul and told her that I wanted to come over with my mother and meet her, with or without her family. She said that I could.

“Now this girl you got involved with. Parul?” my mother asked me over the phone. “Her mother’s flown down from America you’re saying. Is there anything I should know?”

“What do you mean?”

“You know what I mean. Is she pregnant?”

“Oh god, Ma. No. She would tell me if she was.”

We met in Parul’s aunt’s place, my mother and I on one side of the room, sharing a bright orange settee, and her family on the couch that Parul and I used during the days we’d moved in. They served us water and tea, but no food. Parul’s mother presided. Her skin shone like Parul’s; her body was large but soft, covered in expensive looking American material—satiny—and she wore fancy slippers that she tapped on the carpet. She spoke quickly and without smiling.

“The girls in our families are not to be used and left. You might think that is the right thing to do, but that is not what I want for my daughter.”

“She should speak for herself,” I said. “Why aren’t you answering my calls?” I looked at Parul. She did not answer.

“Used? Ma!” she told her mother, “No one used anyone here.”

“I think you should talk to your friend separately.” Her mother nodded at us.

“Mrs. Singh,” she now turned to my mother. “Your son has not been honest with you.”

“Ma!” Parul said again.

“Leave my mother out of this please,” I said, and followed Parul into the dining room.

She closed the door and we embraced. Then she took my hands in hers and said, “There is one thing I want you to know. I’m sorry. I wanted to tell you and I tried, many times, but I couldn’t.

I knew now.

“You have someone else. “

“Before I came to India my parents arranged my marriage with a guy in North Carolina. From the temple. Punjabi, known to the family and all that. I didn’t want it but the families sort of gave each other their word. They’ve known each other for years…an understanding from when we were children. They would let me come here to study only if I agreed to it. We aren’t formally engaged so we never really saw each other, but the plan was that when I went back to Cincinnati we would spend time, date, and then get engaged. I swear, I barely know him. Never tried to get close. Now someone here in Vikasgarh got wind of you and me. Maybe they saw us coming into my aunt’s house. But they told my aunt, and that was why she came home early from her trip. She knew we were here, together. The family of that guy—the guy I’m supposed to marry—if they hear about it in the States, its over for me. We’re not a huge community there. No one there will want to have anything to do with me.” She let go of my hands and began wringing her own. “I wish I had told you. But I couldn’t. I just couldn’t.”

“You didn’t want him. You should be relieved. Why the hell aren’t you telling your family?” I stammered. I could barely hear her now; the blood was rushing into my temples. You wanted me, I wanted to say, but could not.

“It’s not that simple.”

“I don’t care that it’s not simple. Who the hell cares?” I nearly shouted. “You lied. All through. To say nothing to me for three months…” she tried to touch me, but I shrugged her off. “So now what? What are you going to do? Are you going back there with your mother? Parul, please.”

She sighed and did not answer. For long moments we said nothing. She looked away from me, and then back up into my face, her eyes large and entreating, as if there was more she wanted to say. All of her at that moment seemed to converge into a stance of supplication, as if she were begging me to understand her predicament, and though my heart expanded with feeling for her, I could not move. I could not touch her. She noticed this and shook her head hopelessly, placed it in her hands.

“Look,” I had been sitting on a chair at the table. I stood up and went over, touched her hair, ran my hand over it. “Stay back, we’ll give this some time. Don’t go. They can’t make you.”

She shrugged and gave me a look I could not fathom.

“Parul, I came out tonight to tell you to leave with me. You and I have a future, but you have to believe it.”

She paced around the dining table. She was nervous, nothing like the girl I knew two weeks ago. I could hear voices in the living room, her mother was talking. But here, for the first time since we had been together, she was silent. I waited for a while and then said, “Nothing I say is going to make you change your mind, will it? You’re going back.”

The words tumbled out of her mouth. “I had thought I would defy my parents. I thought I would tell you about the guy and plan a way out and that we would make it. I thought I had it all figured out, to tell you when we were at my aunt’s place. But they came back early and found us. I thought we would”—she paused and bit her lip—“elope. Kunal, I can’t… Remember I asked you if you could move to the States? You know I meant it. But it would never work. I cannot let them down. It’s my father, my mother, that’s my life, that’s where I’m going to be. I just cannot.”

We were both crying now.

“You know what you are?” I said finally, “You’re careless. Very careless. Remember this in your new life.”

“Kunal,” Parul came close to me and began rubbing my arm. “You believe me, don’t you? You believe that I meant everything. It was all true. It was all real—I simply fell for you.”

“I believe you. What’s the point?”

The room grew quiet again. I turned my back to her and looked out the window. The street lights had come on. Just a few weeks before she and I had watched them turn on together, from the bedroom upstairs. An ache, fiercer than a blow to my chest, coursed through me. Beyond us was the road, and the shopfronts at the end, lit white with fluorescent lights. I watched people walk in and out of the stores through the revolving door when I realized that I would never again be alone with Parul. I could not know if this thought left her speechless, the way it did me.

She came up behind me and put her arms around my waist. Yet as she unclenched my fists, I knew that her experience of this moment would never be the same as mine, because she had always known that this was how it would end. For the first time since I had been with Parul, I felt then that a piece of me had separated from her, had dislodged and was rushing, falling like debris through space. And yet I could not remove myself from her arms. They were warm around me still, pressing into my stomach through my T-shirt. We stood this way for what seemed a long time, until she disengaged, opened the door, and we joined the others. I moved towards my mother, and she crossed to where her family sat.

Once I had settled, Parul’s mother addressed me.

“The man that Parul is betrothed to is known to us for twenty years. They own two factories, they have stores in Raleigh…they can give our daughter a good life. The life she grew up with. What do you have to offer?

“You should ask your daughter that question,” said my mother.

Parul’s mother ignored her and continued.

“From today on, no contact with Parul. She has a future and she agreed to it before leaving home. We keep our word. We’re good, hardworking people. You can say goodbye, and that is all.” She had the demeanor of a police inspector giving a sermon. “You have a future here. You have a degree in computer science. Life will go on.”

My mother looked at me with sympathy and then replied to her. “I have no doubt life will go on. Please don’t insult us by assuming anything else. It’s our good fortune not to be associated with dishonest people.” She picked up her bag and said, “Let’s go Kunal.”

She was already near the door with her purse in her hand. I looked at her brave little face, the limp, wrinkled silk sari from the two hour train ride to Vikasgarh, her firm, clear voice, and my heart welled with gratitude. But Parul’s mother was not ready to let us go. She took a deep breath and looked around the room, her neck arching like a stork:

“After all, you’re nothing more than a gas guy. I don’t know what my daughter saw in you. I don’t even know why you insisted on meeting us.”

My mother and I walked out through the open front door. When my feet hit the road, it was as if someone had dunked my head in water and yanked it out. Fresh air never tasted so sweet.

“It was all decided a long time ago,” my mother said, gently. “There was nothing that girl could do.”

They say that wisdom comes in a flash and foolishness in great gusts. Miss the flashes and you get lost in the gusts. “Nothing but a gas guy.” Parul’s mother’s words still echoed in my ears. We were already leaving, but those words sent us out of the house; they pierced me and they must have pierced my mother. Yet standing on the sidewalk with her, I remembered something that hadn’t come to mind in the years since I left the U.S.

When I worked at the gas station, a young man a few years older than me, arrived regularly to fill up. He drove a blue BMW convertible. I overheard him tell the guys who worked with me—both Punjabi men in their thirties, with families in India, children and wives, who’d come in on foot from Mexico—that he was from Vikasgarh. He had gone to the same college as I, and had the same degree, in computer science. People drove in and out of the gas station all the time in expensive cars, pick-up trucks, you name it. I attended them as they came, but when the blue BMW convertible showed up, one of my cohorts was always around to fill his tank, to take the credit card. They appeared instantaneously and out of nowhere, making sure I never got a chance to serve this particular young man. It dawned on me that my fellow gas jockeys were protecting me. They didn’t want me filling gas for a guy who was everything I should have been. They didn’t want me to know he existed.

I always took for granted the deference they treated me with, for my education, my knowledge of English. But now it was they that had won my respect, and I had no way of showing them this. I had written off the year I spent pumping gas. But that single memory flashed before me, and I thought, nothing is wasted.

The other flash was Parul herself. It was the last thing she did before we moved out into the living room to join everyone else that night. She threw her arms around me, put her head on my chest and said, “You’re my gift, my mate, you’re decent and good, and I’m a fool to lose you like this.” I did not reply. I had been feeling crushed, bowed down, but I knew then that I would be alright. What Parul and I had lost was precious and stupendous. She came in like a wind, stirred my life, and would go, back to her world, and I to mine. Our lease to each other was brief, and magical. I had an urge to raise my hand and embrace her again, but I did not. I simply let her hold me until she had to let go.

Shaleena Koruth is a freelance writer, graphic designer and MFA candidate in creative writing (fiction) at Rutgers-Newark. She writes about the arts, culture and issues related to the Indian diaspora in the United States. Her work has appeared in Rutgers Magazine, The Atlantic, and other publications.

Ed Kashi is a photojournalist, filmmaker, and educator dedicated to documenting the social and political issues that define our times. He is a member of the VII Photo agency and a founding partner of Newest Americans.

Desi Gas (pronounced they-see-gas) is a blog created by Shaleena Koruth that features short interviews with “desi” gas station workers and taxi cab drivers—immigrants from the Indian sub-continent—telling us the stories of their lives and journeys in their own words.

DESI GAS

The quotes below are from Harsh (Harry), a desi gas station attendant in New Jersey. The photographs are by Ed Kashi.

I’m from Khanna, a small town near Ludhiana. I was studying for a BS in computer science at the time. Jessica came to India to visit her grandparents. Our families knew each other. We liked each other and decided to marry – in a month and a half! My parents said wait for a year until you finish your studies but we decided anyway.

The saddest thing is that I can’t be with my wife because my son needs her care. He’s almost 3. He was born with half a heart. They’ve done two surgeries on him. The third one is coming up. The last one, I hope. Jessica is not working right now. She’s in Florida. I work in Jersey because we have such high expenses and I get paid much better here. I go to see her every two months for 10 days or so.