A Newspaper, A World

In Luso-Americano’s granite and stucco offices on Union Street in Newark, New Jersey, reflective windows flood the building with natural light that has a warm, nearly sepia cast. The light creates a sense of longing to preserve something that is as precious as it is tenuous—a connection to the old country. The employees inside have a pleasing, quiet formality, and the conference room was still, as though time had come here to hibernate. Its walls, lined with cabinets, were decorated with plaques, black-and-white photographs, and a portrait of Vasco Jardim, founder of the Portuguese-American newspaper. An Underwood typewriter sat nestled on a window ledge; it is the same one his American born wife, Angelina, used to provide free translation services to new immigrants.

My host, Maria Do Carmo Pereira, never trained to be a journalist. Somewhere between happenstance and personal choice, her career at Luso-Americano stemmed from a decision to become an immigrant herself, when she stayed on in the United States at the end of a visit to her brother and his wife in Newark, in 1981. She was in her early twenties at the time and near the end of her undergraduate studies in Modern Languages and Literature at the University of Porto in Portugal.

“Back then it was a little easier than it is today,” says Maria, with a smile. “I got my papers very quickly. I was an American citizen in five years. I don’t consider myself like an immigrant because things were so easy for me.” Soft spoken and diminutive, with large eyes and a short mop of light blonde hair, her manner is reserved but warm, without the savvy detachment one might expect from the Associate News Editor at the country’s oldest Portuguese-American newspaper.

“This was my first job, and I stayed.”

– Maria Do Carmo Pereira

When Maria started at Luso-Americano in 1983—writing the classified ads and pieces on cooking and fashion that catered to the paper’s female readers—it was already the most widely read Portuguese language newspaper in the United States. Founded in 1928 in the Ironbound neighborhood of Newark with the mission of creating a House of Portugal—a home for all associations related to the Portuguese-American community—both the paper and the effort to create a cultural epicenter collapsed a year later in the wake of the stock market crash that initiated the Great Depression. On December 7, 1930, the paper was revived under long-time Newark resident Vasco Jardim, Featured on its first page that day, was a story about a project to support the Portuguese community; the building of a headquarters for the Sport Club Português and the Portuguese-American Fraternal Association. Luso-Americano’s promotion of clubs and social organizations like these exemplifies the newspaper’s role in connecting Portuguese in Newark and throughout the American diaspora to their ancestral homeland and its culture.

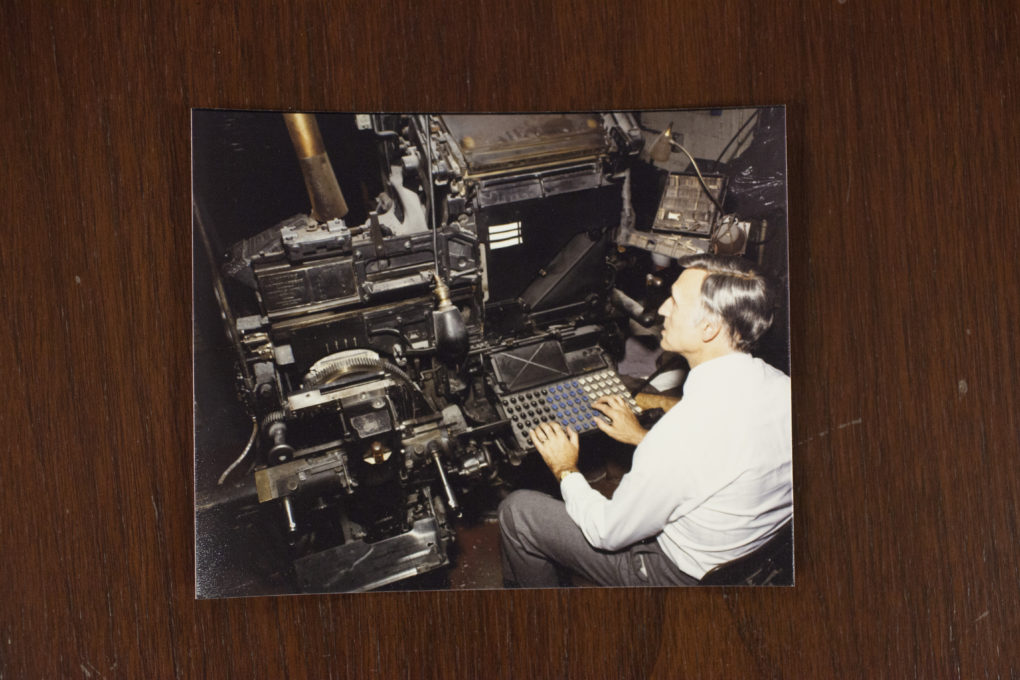

When Maria arrived in Newark, Luso-Americano was a weekly, with a single office on Ferry Street. Today, it has two offices, and is published twice per week. Recalling her first days at the paper, Maria remembers the huge effort that went into producing it. The paper was developed using a phototypesetting process in the Ferry Street office; stories were typed into a computer that created an image of the text on film in a light-proof cassette. The film was processed in a dark room in the basement, to produce lengthy columns of type that were then laid out and pasted on the page, alongside photographs and images, by a team of four to five staff. Back then, before the switch to digital printing off site, the one edition took double the time to produce.

In the earliest years of the paper, Portuguese immigrants were mostly men who came by boat, staying for years sometimes before they could bring their families. Over the decades this changed, as immigrants traveled with their wives and children. Maria’s arrival at the paper in the eighties coincided with a wave of Portuguese immigration into the country. One of her clearest memories is of the office on Ferry Street filling with men and women looking for apartments to rent, every week on the day the paper hit the stands.

“It is the type of paper that we are, a community-driven paper.”

– Maria Do Carmo Pereira

In 1974, during Portugal’s Carnation revolution, the paper was vital to informing immigrants of developments back home. Luso-Americano also serves as a leading informational resource to the Portuguese media in Portugal, for issues related to its expatriate American communities. It is frequently contacted by and cited in Portuguese media, including television news and newspapers.

With the exception of a paid staff of six writers in Newark, the paper’s correspondents, who are spread out across the United States, are all volunteers, most of them office-bearers in the Portuguese-American organizations that Luso-Americano was founded to foster. The paper is divided into sections that publish news and events related to Portuguese communities in cities all over the country, from Mineola, New York to St.Petersburg, Florida to Fresno, California. “It’s the correspondents and the communities and this interaction we have—that’s what really keeps the paper going,” says Maria. She is at a loss to explain how the paper has sustained this model of volunteer writers. “Well, when you love something…” she laughs, and shrugs, as if words fall short of explaining her sentiment.

“Saudade,” says Maria, “is really hard to translate. It’s about a longing for everything that is Portuguese. It could be for food, or friends or even the landscape, everything you’ve known and you remember. It’s about those feelings.” Luso-Americano has always been a “close-to-the-heart business.” The Matinho family, which owns and runs the paper, is there everyday and works closely with the staff to produce the paper.

But with far fewer immigrants entering the States today, and two generations of Portuguese youth whose first language is English, there remains the pressing question of the paper’s future. Luso-Americano addressed this change in readership by introducing an English section in the eighties, but according to Maria, many young people read Portuguese, and are still attached to the language. “We haven’t lost it yet, the youth is still very connected to the country, they travel there with their parents or by themselves. And then, there is the craziness of soccer.” During the World Cup, Ferry Street and its side streets are closed by the police. People come out with flags, celebrating and cheering. “It keeps the youth really involved. This part of Newark goes crazy!”

Even today, despite Skype and the collapsed boundaries that the internet has facilitated, the paper plays an important role. “Wherever there are Portuguese, there are subscribers,” says Maria, “they still need the paper to feel connected and to keep in touch with one another.”