Meanwhile In Brazil . . .

. . . people are protesting. Millions of people. But the internet is focused on these people in particular.

That’s Claudio and his wife Carolina Maia Pracownik, a wealthy white couple at a protest in Rio. Trailing behind them is Maria Angelica Lima, a domestic worker who cares for the Pracownik’s children on the weekends. Admittedly, I was taken aback by the photo. In all my years learning about the history of radical protest from family members, community elders, and libraries, I have never seen anything like it.

While I didn’t know what to think about the photo, the rest of the world was pissed. The photo, and Lima, became symbolic of racialized economic inequality in Brazil, the last country in the world to abolish slavery.

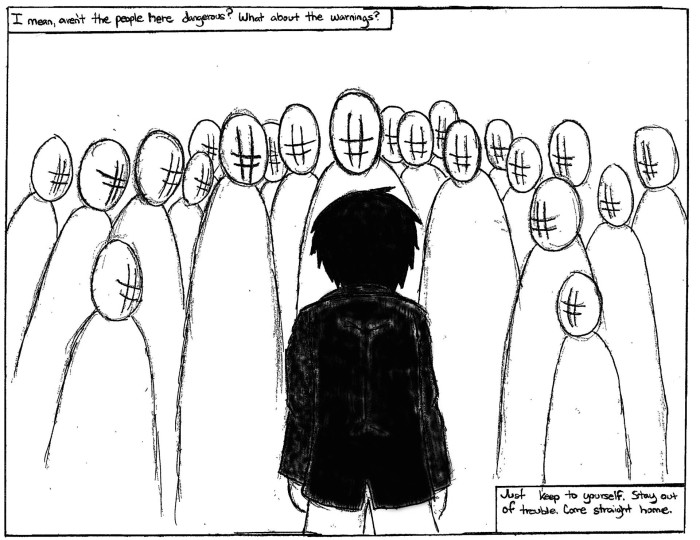

Ana Lucia Araujo, professor of history at Howard University and a scholar of cultural representations of Brazil in our collective historical memory, tweeted this political cartoon from 2015 in response to the photo, which she considered emblematic of the profile of the protestors from the March 2016 demonstrations.

Just like that a viral sensation was born. The two photos have been retweeted, reblogged, memed, facebooked, editorialized, youtubed, hashtagged, and engrained in the Brazilian public imagination. And every article says the same thing. Massive protests across the country. Demanding the impeachment of the president. Demonstrators are white. Upper middle class. College educated. They are against corruption in the government. But look at this photo! The hypocrites! They want a less corrupt government, but not an equal society!

The Pracowniks didn’t help the situation any. They emphasized that they were creating jobs in a country plagued by unemployment. Savior complex much?

As usual, the domestic worker got lost somewhere in this conversation. Maria Angelica Lima became the black nanny. Her existence, evidence of economic inequality. When I see her, I see a working woman walking with her shoulders back and head held high. But the rest of the world, even when they think they are coming to her defense, see the diminutive and victimized woman in the cartoon, who looks almost childlike and afraid.

So what happens when you give voice to the often nameless, faceless, and silenced domestic workers who become viral sensations? Well, things get a bit complicated.

A Brazilian journalist did manage to find Lima and ask her how she felt about her newfound internet fame. She explained that she felt exposed. Her bosses were exposed. And, most importantly, their children were exposed.

Is she being exploited? She says, her employers pay her well above the wage typically granted to domestic workers in the country.

As for the white uniform she wears, which the internet considered a symbol of her degradation: It is provided by her employers and keeps her from messing up her clothes.

Lima actively participates in electoral politics. She is also against the current administration in Brazil, albeit for different reasons.

But on this day, she says, she was working. The same thing she does every Sunday for the Pracowniks, when there are no journalists around to photograph her.

Oh, and when she and her husband are both working they, too, employ a nanny to take care of their children.

Uh oh.

So what do domestic workers in Brazil think about this picture? When the photo was posted on the facebook page Humans of Protesto, domestic workers took to the comments to share their thoughts. Like every domestic worker activist I have ever encountered, each woman unapologetically identified herself as a domestic worker and one who does that job with pride and dignity, the same as Lima.

And this, my friends, is what happens when we sound off about domestic labor without looking for guidance from the women who do the work. We end up telling these stories of struggle without giving their protagonists the respect and admiration they deserve. Domestic workers are not a silent symbol of global inequality and oppression. Their eyes and their words are a lens through which we can understand these dynamics while also seeing what effective resistance looks like. One can be both oppressed and dignified. One can be proud of their work at the bottom of the class hierarchy. It all depends on who’s telling the story.

Words: Shana Russell

If you like what you read, check out Shana’s Maid in the USA blog.