THE VILEST SWILLHOLE IN ALL OF CHRISTENDOM

Shortly after Alexander Hamilton was appointed the United States’ first Secretary of the Treasury he co-founded the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures, which in 1792 purchased 700 acres of land surrounding the largest waterfall in New Jersey. The land was used to establish the city of Paterson, Hamilton’s incubator for a “New National Manufactory” that would provide economic independence for the United States by stimulating the transition from an agricultural to a manufacturing-based economy.

An immigrant from the British West Indies, Hamilton envisioned an industrial future predicated on the waterpower provided by Paterson’s Great Falls and the immigrant imagination and labor to harness it productively. In his “Report on Manufacturers,” Hamilton wrote that to create an industrialized nation would require “the promoting of immigration from foreign countries” and “the furnishings of greater scope for the diversity of talents.” Patterson was the demo site for Hamilton’s vision, which proved to be pretty much 20/20. Chances are if you knew a wealthy industrialist in 19th century Patterson they had something in common with Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton—an immigrant of dubious lineage, but with mad skills, ambition, and grit. Someone who had not given away their shot.

Fed by the Passaic River, the Great Falls of Paterson would provide the power source for industrializing northern New Jersey. From Paterson’s 19th century textile mills to Newark’s 20th century chemical manufacturers, the Passaic has been the epicenter of the region’s prosperity. The riches produced by the waterfall, however, came at considerable cost to both the river and the recurring waves of immigrant laborers and entrepreneurs who found their land of opportunity along the Passaic.

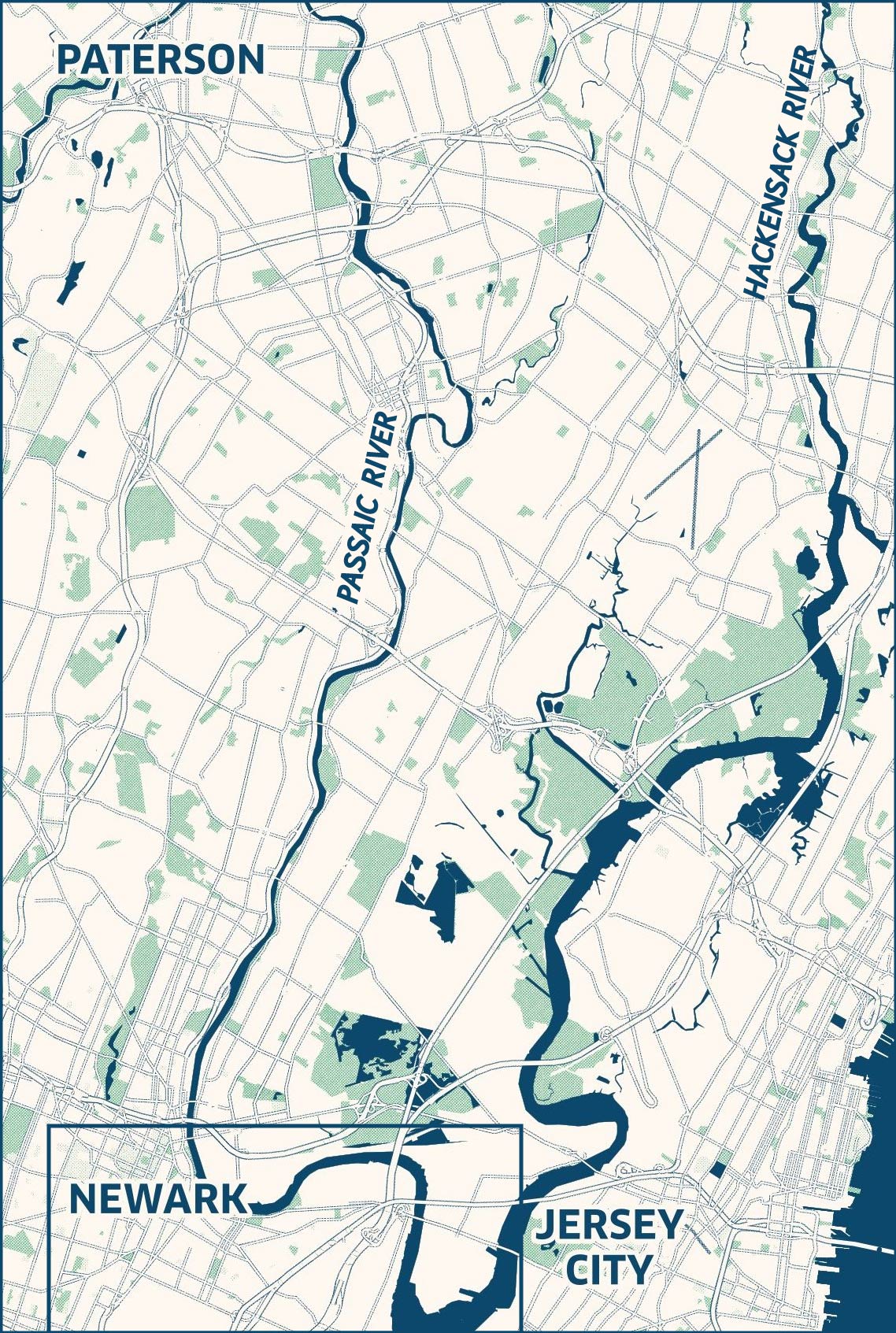

The Passaic spans 80 miles as it crisscrosses northern New Jersey before emptying into Newark Bay. “Passaic” is a Lenape word that roughly translates as “peaceful valley river.” Upstream from Paterson, this is still a relatively accurate description for a tributary that provides drinking water to 4 million people. The lower Passaic, from Paterson downstream through Newark, is an altogether different story.

What is shocking is how long people have known what industrial production was doing to the Passaic, and how little was done in response. At the end of the 19th century, journalists were already writing about the “flood of filth” pouring into the river from Paterson’s silk mills, tanneries and slaughter houses. In the 1890s, the bacteria created by industrial waste and circulated by the river made Newark’s death rate from typhoid among the highest in the nation. By the 1940s, the effects of industrial pollution inspired poet William Carlos Williams to characterize the river as “the vilest swillhole in all of Christendom.” In his epic poem “Paterson,” Williams describes the toll industrialization had taken on the Passaic:

Half the river red, half steaming purple

from the factory vents, spewed out hot,

swirling, bubbling. The dead bank,

shining mud.

The past 50 years is a sad tale of big promises and little action. When Richard Nixon established the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970, one of the first initiatives announced by the EPA was to turn the Passaic into a model river. That did not happen. In 1984, the Passaic was named a Superfund site in recognition of its status as one of the nation’s most polluted waterways. It remains so today.

While there are many toxic pollutants in the Passaic that pose challenges for remediation the most daunting is dioxin, a byproduct of the manufacture of Agent Orange, the toxic defoliant infamously sprayed on farms and fields during the Vietnam War. The most potent form of dioxin was manufactured along the banks of the Passaic at the Diamond Alkali plant in Newark. It is now embedded in 17 miles of the river’s sediment and has leeched into the groundwater.

The EPA warns that short-term exposure to dioxin can cause skin lesions and altered liver function, and long-term exposure can cause reproductive and developmental problems, disruptive hormone function, damage to the immune system and thyroid function, and cancer. The first sentence of the EPA website’s Clean-Up Information statement for dioxin offers little solace. It begins, “Remediation technologies for the cleanup of dioxin-contaminated soils and sediments are still being developed . . .”

Alexander Hamilton’s vision of an immigrant-driven industrial revolution came to pass along the banks of the Passaic River. Hamilton’s Society for Establishing Useful Manufacturers offered resources that lowered barriers to entry into manufacturing for people who lacked access to capital. It provided the land, factories, and power needed to incubate new businesses, generate sustainable employment, and build schools, towns and cities. The Passaic made all this possible.

In March of this year, the EPA announced a $1.4 billion dollar plan to clean up the lower eight miles of the Passaic—one of the most ambitious and expensive efforts in the history of the federal Superfund program. EPA officials estimate the cleanup will take 11 years to complete. They caution that the fish in the river will still not be safe to eat when the cleanup is completed.

“The reason this city was founded was the Passaic River. It was our lifeblood!”

Cory Booker

0:56

“Why would anyone want to come out here?” says a woman in the office, “It’s dangerous, it’s polluted, you shouldn’t walk around here after dark. Frankly, it’s creepy.”

I’m at ISS Logistics, a trucking company that’s owned and run by a Guianese family that’s been emigrating in dribs and drabs to the United States over the past 20 years. It’s hard to hear anyone here—every two minutes, just a couple of hundred feet above us, plane engines roar as they make their final approach to Newark airport. It doesn’t really matter though, because no one here wants to talk—they’re all super cagey.

No one will tell me their names, their work hours, the nature of the business. Some of the employees won’t even make eye contact. They don’t understand why I’m out there photographing the place, and it’s only after my sixth visit that the lady in the office, owner Indrawattie Ramlakhan, asks if I’m doing some type of secret work.

David, Indrawattie’s brother, is my main contact. He’s a mechanic and security guard at the site, and appears to be equally suspicious. I turn up day after day to see how he’s doing, only to be met with some variation of “Too busy, I’m too busy. We’re moving soon. Got to get ready. Too much to do.” When I ask, multiple times, where ISS is moving to I’m given a suspicious glance, “Somewhere in Newark,” I’m told once.

David sleeps here above the office most nights, even though he maintains a home for his family in Rockaway, New York. For the past two weeks, he’s been joined by his cousin, another mechanic who, according to another employee, “is fresh off the boat” from Guyana. Every night, at around sunset, two other men mysteriously appear at the front gate where they sleep in their cars.

One morning, I arrive early, and go upstairs to see if David’s awake. I knock on his door, which is wide open, but there’s no answer. Poking my head into his room I see an unmade bed and an otherwise empty space, but on my way out I notice something through the crack of the doorway. Standing in the small space made by the open door and the wall is David. He’s standing there in his underpants, looking straight ahead at the back of the door. I call out his name. No response.

For almost an hour, I sit outside the door in an adjoining room in which his cousin is sleeping. He doesn’t stir as the planes fly in overhead. Every fifteen minutes I knock on David’s door and call out his name. No response.

The company, which trucks containers from the Port of Newark to destinations all over the Northeast, has been based on a plot of land between Lister Avenue and the Passaic River for the past five years. The office is in a newer looking building, but the workshops are in former factory areas that once belonged to the Hilton-Davis chemical company. Immediately next door is the former site of Diamond Shamrock, which manufactured Agent Orange during the Vietnam war and was renowned for producing a more potent, dioxin-rich version of the agent than any other producer. The Diamond Shamrock site was so heavily polluted the land was sealed with plastic sheeting and rocks to prevent further contamination of the soil. Over the southern fence is Chemical Waste Management. There, every other day, a man who’s worked there for 50 years, comes to make sure there’s no still water on the site.

David’s not moving, so I go downstairs. I nod hello to one of the men who’s waking up in his car. He’s a tall, fit African in a big, old SUV. He doesn’t respond either, so I walk down to my car and sit on the hood and smoke. After a few minutes, the SUV pulls out and makes a three-point turn to line up with me. The engine revs and its tires kick up dust and stones and it’s bearing down on me, engine screaming. At the last moment, it pulls out of the way to avoid ramming me. The man looks upset, and he presses a button to lower the window. “You finish taking photos.” He tells me, “You don’t know what is coming to you.”

I’m confused, so I ask what he’s talking about. A tirade follows: about how things in Africa are different, how America is not fair, how I’m his enemy, and about what’s going to happen to me—and it’s not pretty. The exchange ends when the man gives me his business card and tells me if I need anything, cars, trucks, transport, that I should call him. He revs the engine again and he’s off.

“That’s Nana, he does that to everybody.” I’m told later in the day.

On the front entrance of ISS Logistics, a large sign affixed to a wire fence by the Environmental Protection Agency says an investigation and cleanup is taking place on the site. When I reach the investigating officer on the phone, he tells me the ground is still filled with deadly toxins and the site is supposed to be sealed at all times to contain the contaminated soil. Above the sign, weaving its way through the wire chain is a vine, and it’s bearing fruit.

In most places, the yard is indeed mostly sealed. Tractor-trailers are all over, squeezed in among piles of torn up cement, dirt and abandoned rotting hulks of cars and trucks. There’s even a boat on one pile. Among the trucks and refuse, there are plants. Some of them are the tall wild weeds that flourish in forgotten, uncared for places like this, but some of them are quite the opposite. There’s a vegetable patch, lovingly cared for by the entrance, and fruit grows throughout the site.

Cherry tomatoes are growing out of soil that’s been heaped into old car tire rims, but the Chinese cucumber and the Italian squash are growing right out of the soil that’s been exposed by cracking cement and bitumen on the ground. There’s an eggplant vine that runs rampant amidst the smashed concrete and waste next to the old factory.

I’m here on David’s invitation to see him harvesting some of the fruits and vegetables before they move. His garden is David’s pride and joy, and when he talks about it he smiles–a rarity otherwise–and becomes animated. “I give the vegetables all to my friends and my family,” David says. “It’s so good.”

He’s having trouble finding the time though. “So busy. So much to do,” he keeps saying. It’s a mantra. I’ll be photographing him working on a truck when he gets up and says he’ll be back in a minute, and then he disappears for the rest of the day.

At one point, I’m in his workshop where he’s looking for a bungee cord when he walks out of the space. I watch him leave and after a few minutes I walk through the maze of the old factory to see if he’s out back.

I’ve done this before, but this time I get lost and end up in a dead end room. There’s paint peeling from the walls, and nothing on the ground. There are marks on the wall from some sort of machinery that used to be there. There are no windows in here, but one wall has been smashed in, and light enters the little space from an adjoining room—the one I was supposed to be walking through.

I turn to leave when I notice David, pressed into a corner, standing with his hands by his sides, staring ahead of him, expressionless. I apologize for intruding and leave. He follows me a few minutes later. “Got to feed the baby cat,” he says, apparently to himself, before dropping a bowl into a big bag of dry cat food and leaving it there.

As the day draws to a close, I notice empty beer cans have begun to pile up around the worksite, focused mostly around the garden area in the front. David’s here, and he walks into the office and emerges with a large pair of metal scissors. He starts cutting eggplants, and then calls his cousin over to help him climb the fence to get access to an enormous Italian squash that’s growing on the old Diamond Shamrock side.

His cousin climbs a ladder, carefully cuts the stem and passes David a four-foot-long squash. David is smiling as he studies the fruit before stepping back, looking into the camera, and striking a pose.

“Call me in three weeks. You can come visit the new place,” he says, before getting in his truck and disappearing again.

Ashley Gilberton, VII photographer, is a core contributor to Newest Americans.

Ed Kashi, VII photographer, is a founding partner and core contributor of Newest Americans.

Tom Laffay is a visual journalist based in Central and South America.

Tim Raphael founding Director of the Center for Migration and the Global City at Rutgers University-Newark, is a founding partner and Executive Director of Newest Americans.